Oil prices have collapsed by as much as 30% in response to a reduction in offered prices and increase in supplies by Saudi Arabia. Those have reportedly been launched in response to Russia’s refusal to cut oil supplies in response to the drop in demand caused by the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak, S&P Global Market Intelligence reports.

There are at least four potential knock-on effects for international trade.

Global trade takes a hit, not everyone loses

First, the value of global trade will take a marked step down given the importance of the oil trade – it totalled 6.4% of global exports in 2018, Panjiva’s macro data shows. That was up from a trough of 4.4% in 2016.

A large part of the recovery was down to an increase in average oil prices – volumes shipped only increased by 4.4% between 2016 and 2018 while average prices per ton surged 69.6% higher.

Source: Panjiva

Unsurprisingly the oil producing states such as Iraq and Saudi Arabia are most exposed from an export perspective – oil represented 94.1% and 65.1% respectively of their total exports in 2018. Outside the middle east Russia (31.9%) and Norway (30.4%) have the most to lose from lower oil prices.

The U.S. and Canada have a degree of balance. The U.S. shale oil boom has meant that exports of crude oil represented 4.1% of total exports in the 12 months to Jan. 31 while crude also accounted for 5.1% of imports. The mix is due to refineries’ differing needs in terms of grade of crude oil as flagged in Panjiva’s research of Nov. 29. Crude oil represented 13.8% of Canada’s exports and 3.3% of imports for similar reasons.

The largest importer in absolute terms was China, with crude oil having represented 12.1% of total imports in 2018 while in proportional terms India was among the most exposed at 22.9% of imports. The latter should therefore see a significant drop in import costs – the largest importers in the 12 months to Nov. 30 included Indian Oil, representing 27.3% of imports, Bharat Petroleum (14.5%) and ONGC’s Hindustan Petroleum (13.2%).

Source: Panjiva

U.S. export growth could hit pause

Aside from cutting the absolute value of trade, the slide in the oil price removes a significant growth driver for U.S. exports. Panjiva data shows that U.S. oil exports reached $67.2 billion in the 12 months to Jan. 31 after growing by 88.3% annually for the past three years. In dollar terms the rise of $57.2 billion accounted for 31.1% of total U.S. export growth over the same period.

Aside from the dollar value effect of lower prices, there’s also the potential for drilling company bankruptcies which would cut the volume of output according to S&P Global Platts.

The net effect on the economy, as flagged above, will be somewhat mitigated by the decline in oil import costs. Leading seaborne importers of crude oil to the U.S. by sea in the 12 months to Jan. 31 include shipments linked to Valero worth 22.7 million tons imported followed by Chevron with 18.2 million tons and Phillips 66 with 18.1 million tons.

Other knock-on effects to U.S. trade will include lower values for refined oil products and potentially liquefied natural gas where some global contracts are linked to oil prices (though many U.S. export contracts are linked to Henry Hub gas prices).

Overall the U.S. imported $223.8 billion of crude oil, refined oil and natural gas in the 12 months to Jan. 31 while exports $196.9 billion of the same. The balance of a net import of $26.9 billion included net inflows of crude oil worth $71.5 billion and exports of $34.8 billion of refined oil – the value of which will likely fall with lower crude prices – and a net export of $9.8 billion of natural gas via pipelines and LNG.

Source: Panjiva

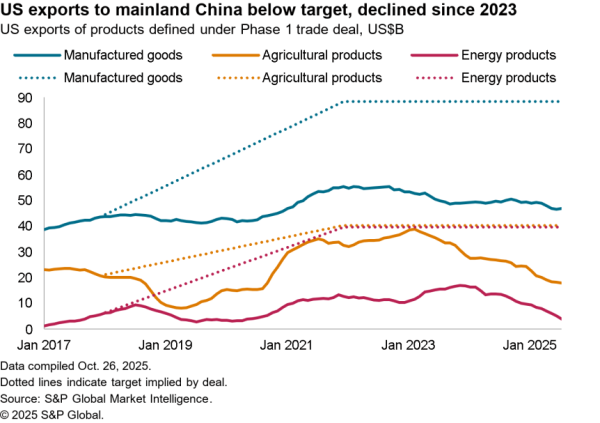

China might miss its phase 1 commitments (by a wider degree)

Second, China will be even less able to deliver its phase 1 trade commitments. As flagged in Panjiva’s research of Mar. 9 above it was already going to struggle with the drop in demand caused by the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. The U.S. may yet give it a pass / roll forward commitments made, though the U.S. Energy Secretary, Dan Brouillette, has stated that he is confident China will meet its commitments.

One option for China is to redirect the bulk of its energy purchasing to the U.S. Panjiva’s analysis of official data shows that China imported $238.7 billion of crude oil and $41.9 billion of natural gas in 2019. The phase 1 trade deal commitments require $26.2 billion of energy imports (coal, gas and oil) in 2020 and $41.6 billion in 2021. Putting aside the drop in oil prices – which could be used to adjust the commitments downward – China would need to reallocate 9.3% of its purchasing for the year.In January imports were just $26 million.

China’s imports have continued to increase in 2020 even allowing for the coronavirus outbreak – imports of crude oil increased by 5.2% volume terms and 14.7% in dollar terms in January and February combined while natural gas increased by 2.8% in volume terms but fell by 16.0% in dollar terms due to lower oil prices.

Source: Panjiva

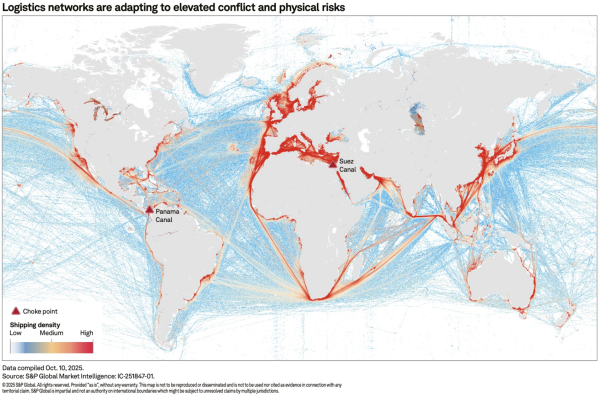

Global shipping – unwelcome volatility

In theory lower fuel costs should be beneficial for the industry – bunker fuel is refined crude oil – though the impact on corporate financials will be a function of hedging arrangements.

Specifically bunker adjustment factors for shipping rates are normally updated on a three month-trailing basis – it could be May 1 before term-contracts adjusts. Panjiva’s analysis of S&P Global Platts and S&P Global Market Intelligence data shows that the three month rolling average bunker fuel price has fallen by 2.2% year-to-date while the WTI crude oil price fell by 1.7% on the same basis.

For spot rates the container lines are already under pressure to maintain rates at current levels due to the loss of demand resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak.

It should be noted that the last time oil prices dropped to current levels in 2015 / 2016 there was the collapse of the Hanjin Shipping corporation. This time may be different – the price drop is supply rather than demand led.

Source: Panjiva