The first, long-awaited, round of negotiations to reform the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) run from August 16 to 20 in Washington, DC. There are expected to be seven rounds of talks, each running for up to five days at three weekly intervals. The initial talks will focus on what areas may be included, or excluded, from the remainder of negotiations.

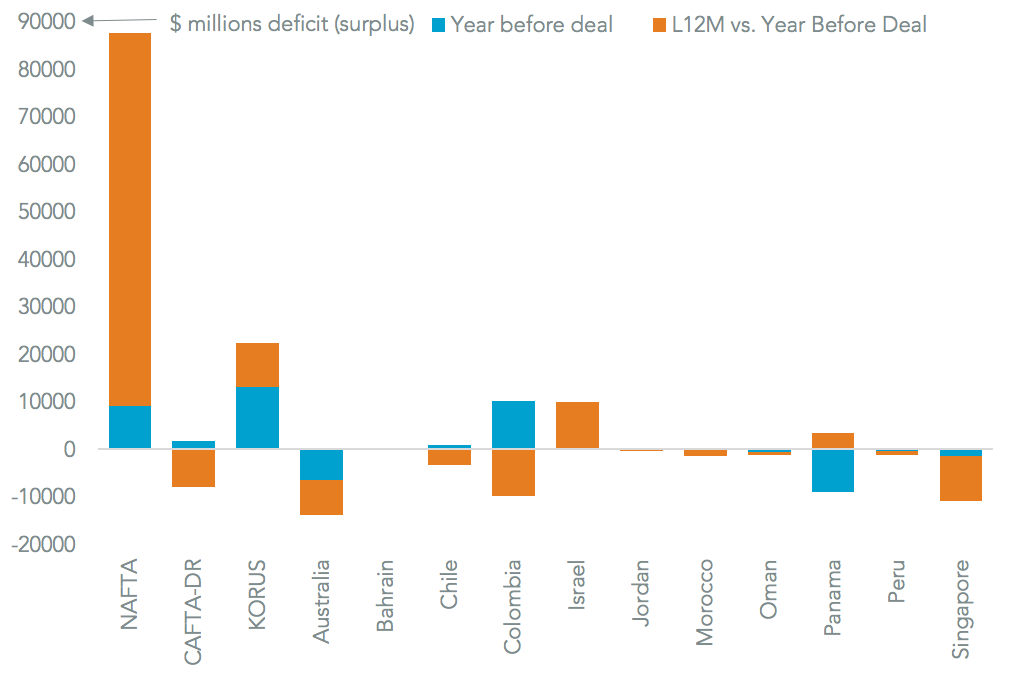

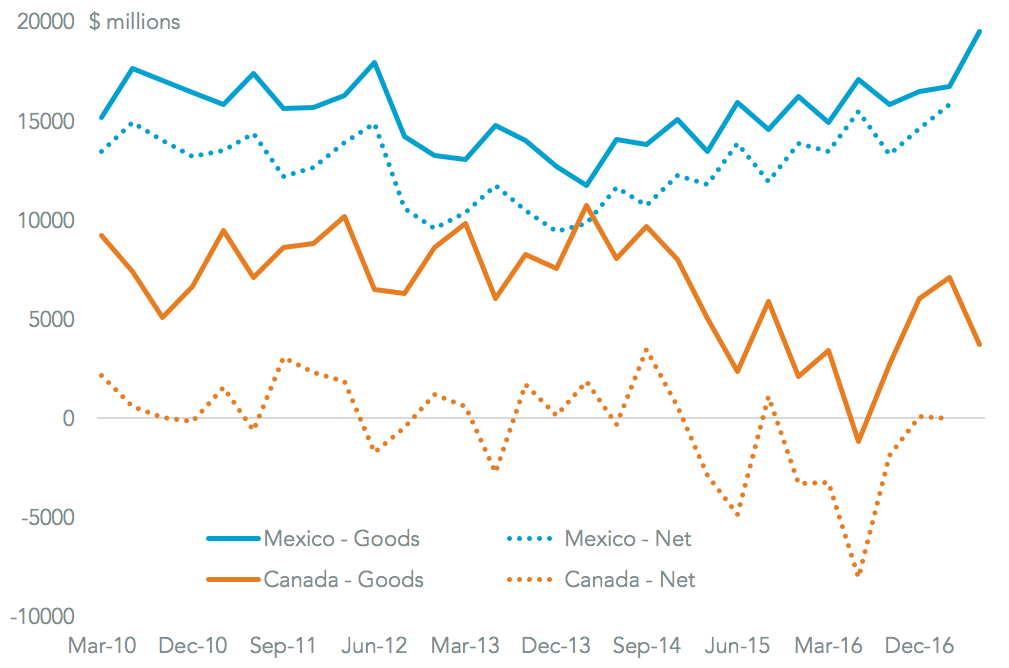

The central challenge for the talks – and the proximate reason for the start of negotiations – is that the administration of President Donald Trump considers the original NAFTA to have failed on the grounds of an expanded U.S. trade deficit. The focus on the trade deficit, specifically goods, is the key performance indicator for the USTR’s broader review of trade deals, as outlined in Panjiva research of May 2.

In that regard NAFTA is clearly a “failure” – the trade deficit (based on goods exports less imports) reached $87.8 billion in the 12 months to June 30 vs. $9.1 billion in the 12 months up to NAFTA coming into force in January 1994. It’s worth noting that U.S. exports to NAFTA increased 5.6% on a compound annual basis since then, compared to 5.2% for U.S. exports globally – including 7.7% with Mexico and 4.3% with Canada.

Source: Panjiva

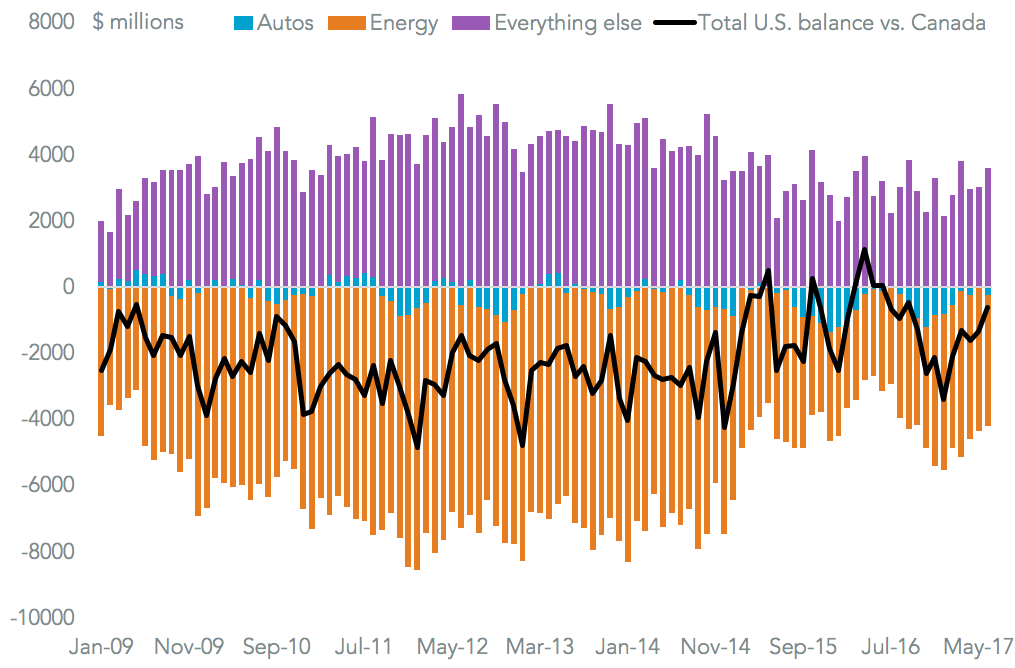

If judging relations purely on the basis of the trade deficit, U.S. dealings with Canada are already successful, excluding energy. In the 12 months to June 30 the U.S. had a $18.7 billion deficit with Canada. This included a $48.5 billion deficit in energy, i.e. all energy exports including coal, gas and oil net of imports. That was significantly narrower than the $83.7 billion prevailing in 2012, and is largely a function of the oil price. Given the Trump administration’s energy policy aims for energy independence from OPEC, it is difficult to see NAFTA being changed in a way that would reduce Canada’s energy exports.

Taking “everything else” (outside autos as discussed below) the U.S. actually ran a trade surplus of $35.7 billion. Given the Canadian government’s main “asks”, as outlined in a speech made on August 14 by Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland, are related to non-goods policies there shouldn’t be too much controversy between the two countries on the goods chapters.

Source: Panjiva

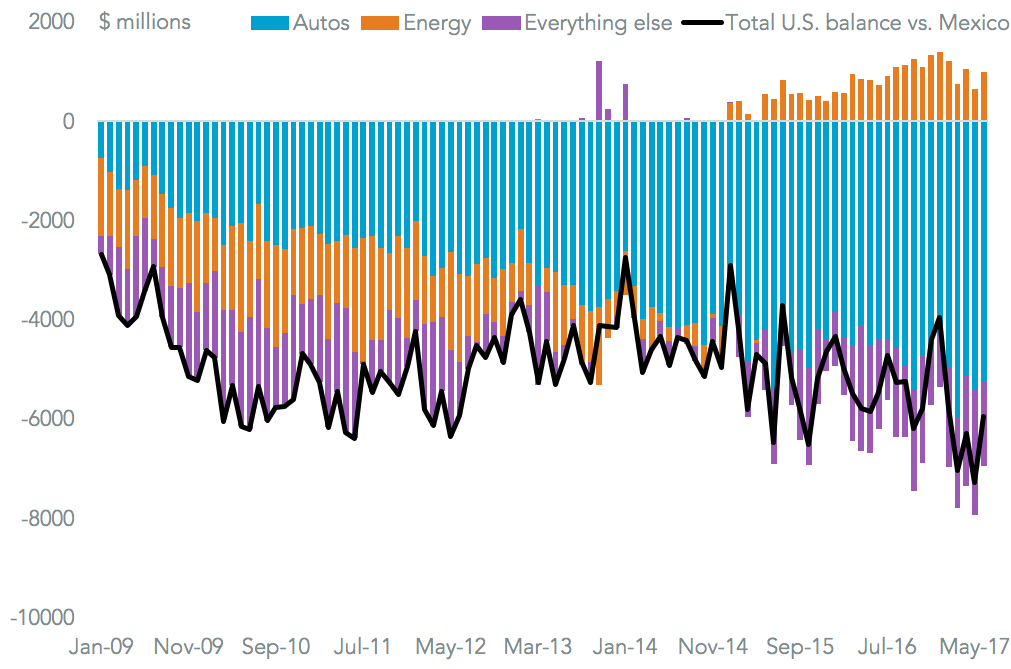

The U.S. deficit with Mexico reached $67.9 billion in the past year, of which the automotive industry – including imports and exports of completed vehicles and components, reached $59.6 billion. That was 1.74x the level seen in calendar 2012, and made the auto sector a center-piece of President Trump’s campaign and pre-inauguration trade rhetoric.

It has also driven companies to alter their investment policies at the margin, as shown by General Motors’ in-shoring of parts manufacturing and Fiat-Chrysler’s truck-manufacturing shift. Yet, imports from Mexico may naturally slow as U.S. car sales drop. They have already fallen for seven straight months, though so far Mexican exports have remained robust.

Source: Panjiva

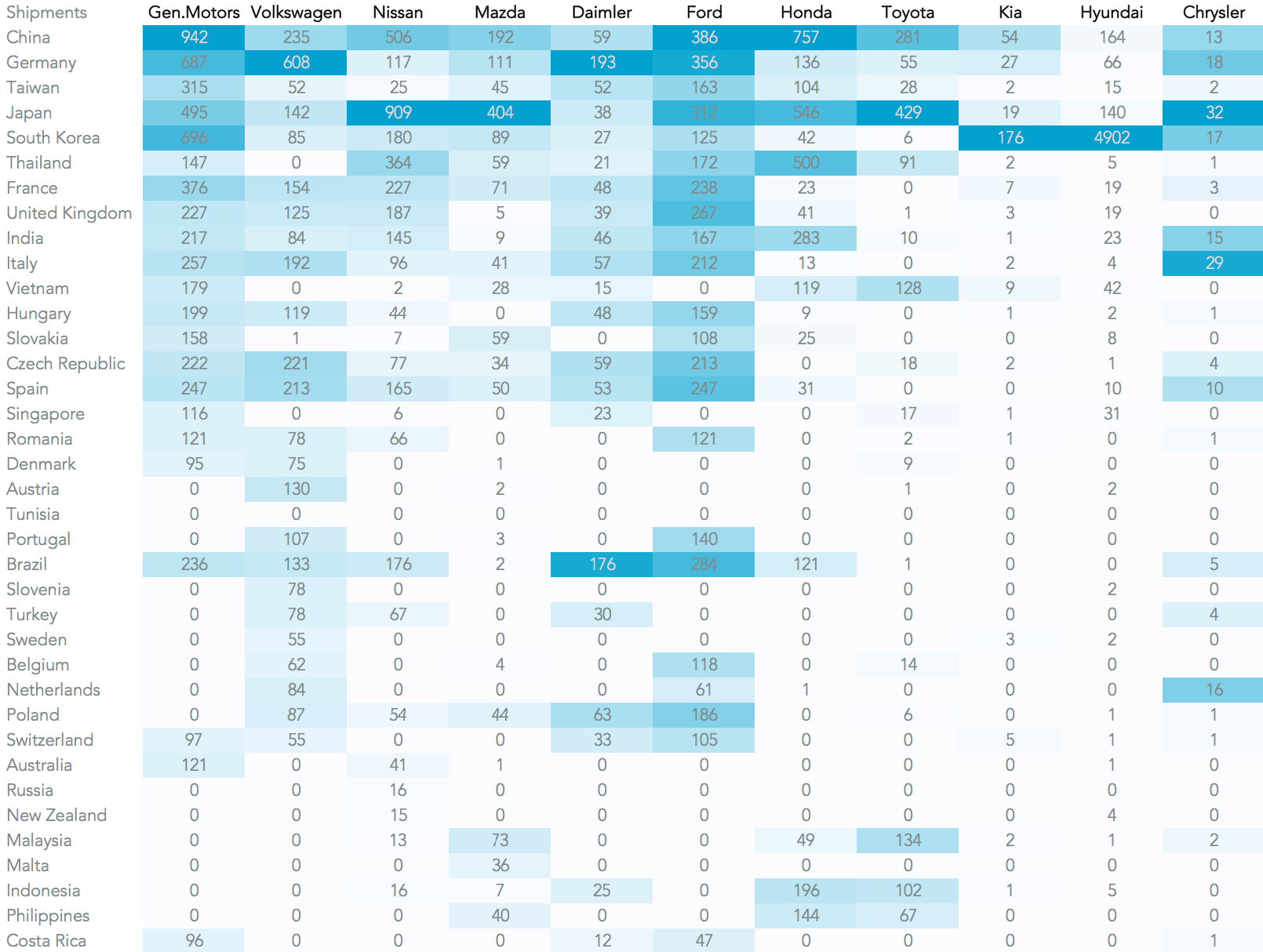

One option may be to encourage more parts manufacturing in the U.S., rather than trying to force the relocation of final assembly from Mexico. That could be handled via changes in the rules-of-origin embedded in NAFTA. The current rules are based on an aggregate “regional content value” of 62.5% for a vehicle to be counted as NAFTA-produced (and hence tariff free) based on a list of parts established when NAFTA regulations were written.

An expansion to include modern parts – particularly electronics and hybrid drivetrains – could automatically result in a need to in-shore more parts production from outside NAFTA, even without changing the 62.5% threshold.

Panjiva analysis of 1,150 country-product pairs shows 21.0% of Mexican parts imports by the top 11 manufacturers came from South Korea (Hyundai), 11.9% from China (General Motors and Honda), 11.5% from Japan (Nissan and Toyota) and 7.9% from Germany (Volkswagen and General Motors).

Source: Panjiva

The NAFTA negotiations will not be limited to trade-in-goods, however. The U.S. ran a trade surplus in services of $6.9 billion with Mexico and $24.5 billion with Canada in the 12 months to March 31, BEA data shows.

That’s equivalent to the entire goods deficit in the case of Canada and just 6% in the case of Mexico and covers a broad range of industries including banking and insurance, software, intellectual property, telecoms and maintenance/repair. Expanding services exports, particularly to Mexico, via liberalization of professional standards may be one – admittedly complex – area for negotiation.

A reduction or adaptation of regulations more broadly is also an aim for Canada, including removal of local provision rules for state-owned activities. That could easily run afoul of the Trump administration’s “Buy American” policy objectives however.

Source: Panjiva

Development of a full range of updated, and new, chapters for regulations outside of the trade-in-goods could prove to be the negotiations’ undoing – at least in terms of completing talks before the end of the year. Ironically, dispute settlement could be at the center of the problem.

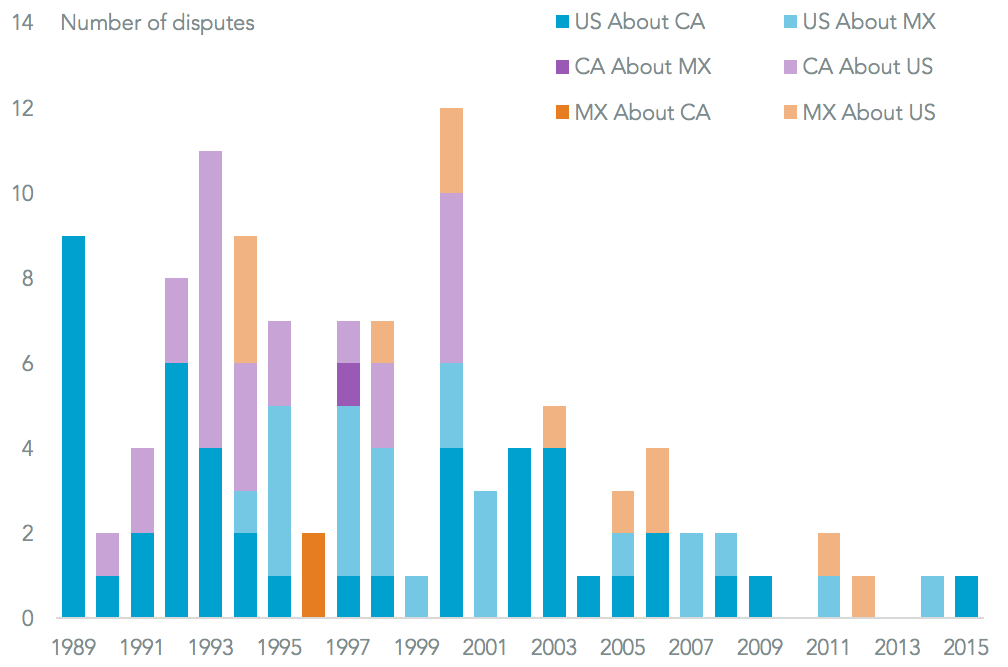

The Canadian and Mexican governments want to maintain the existing chapter 19 review process, including state primacy in investor-state dispute settlement. The U.S. is ambivalent, though ironically it has been the biggest user of the existing system with 64.2% of challenges since 1989 through the last submission in 2015, Panjiva analysis of official records shows.

Further complexity may come from Canadian commitments to: improved labor standards; inclusion of environmental protection provisions; creation of new chapters for gender and indigenous peoples’ rights; removal of local provision rules (like “Buy American”).

The EU-Canada CETA trade deal is held out as an example of what Canada is looking for, but that took years rather than months to formulate. It is unlikely that the Trump administration would have patience for such a protracted process, even if was in accord with the general concept of the chapters Canada is looking for.

Chart shows appeals to NAFTA dispute panel by year. Source: Panjiva

As a final area of complication the U.S. has a number of other trade cases running as well as the ongoing performance review of all its trade deals and a broader review of the defence manufacturing industry. That further further limit areas for transactional deals on specific products. One prime example is softwood lumber, which accounted for 2% of Canadian exports to the U.S. in the past 12 months.

Finally, Panjiva analysis of each countries’ top 200 trade lines shows there is two-way trade in 42.9% of products. Those are areas where discussions will either need to be trilateral – and hence more complex – or where countries will need to make “product specific” trade deficit judgements. That will prove to be particularly complex in the consumer electronics industry, and in particular in communications and information technology sectors.

Source: Panjiva